Join the Club: Faculty Member Joy Agner Mobilizing Knowledge about the Clubhouse Model to Support People with Mental Health Conditions

By partnering with a community organization, one USC Chan faculty member demonstrates how to engage a user base, develop a collaborative research agenda and put knowledge to work for the people who can most use it.

By Katharine Gammon

Before she found Sheldon Clubhouse, life posed constant challenges for Leasa Holton. Managing mental illness led her to repeated hospitalizations over two decades. But discovering the mental health “Clubhouse” in her area, a place where she could go every day to work and socialize, was a game changer.

“I came into Clubhouse because it was a safe space for me,” Holton says. “I can do work here, be involved here, and I’m always welcome from the minute I come in, right until the time I leave.”

Clubhouse International is a non-profit organization that expands and enhances recovery opportunities for people living with mental illness using the proven Clubhouse Model of psychosocial rehabilitation. More than 360 Clubhouses in 33 countries around the world offer safe, welcoming environments in which people can work, socialize and actively participate in their own recovery.

Clubhouse members at Stepping Stone, a Clubhouse International-affiliated organization in Brisbane, Australia, which describes itself as dedicated to suicide prevention and to ending social and economic isolation for people living with mental illness (photo courtesy of Clubhouse International)

Joy Agner, an assistant professor at USC Chan, specializes in community-based participatory research, working hand-in-hand with Clubhouse stakeholders, staff and members like Holton. CBPR empowers people to formulate the questions to conduct research that matters most to them.

But over years of collaboration, Agner has seen the gap between research about Clubhouses and organized efforts to increase its scale, advocacy and reach. While there’s ample research out there, she says, it can be frustratingly hard to access when locked behind paywalls or full of academic jargon.

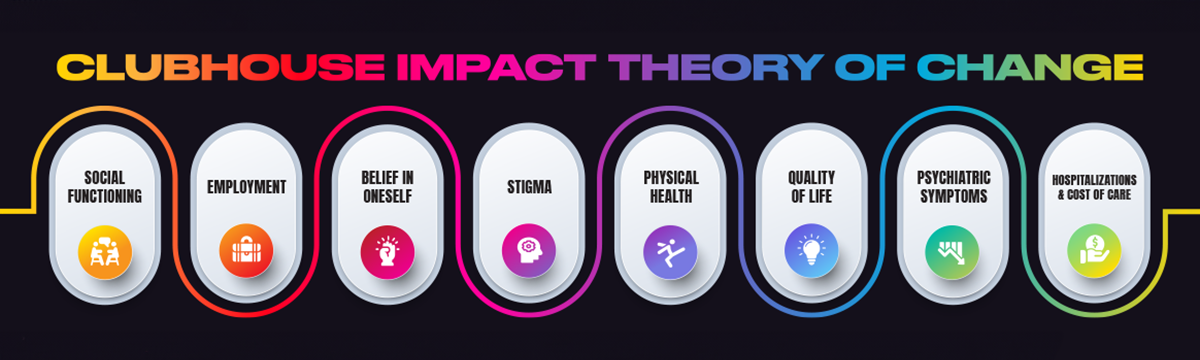

So in addition to doing her own research, Agner and her student researchers Elizabeth Bau OTD ’25 and Yongshi Wang OTD ’23 put together a comprehensive review of the existing research literature about Clubhouses in a user-friendly, graphics-forward, customizable format. “Transforming Lives: Clubhouse Impact Report” integrates findings from 15 peer-reviewed studies conducted between 1999 and 2021. Agner and her team combined findings to create what she calls an “integrated theory of change” that explains how and why the Clubhouse Model works.

The report highlights the direct impact Clubhouses have on their members. For example, research shows Clubhouse members were much more likely to be employed after six months of attendance, as compared to individuals who received psychoeducation. Clubhouse members sustained employment longer than those who received assertive community treatment. Members’ quality of life was also much higher than individuals who attended an outpatient clinic, and those who sustained Clubhouse membership over two years reported fewer hospitalizations — which means lower total costs of their care.

Many people experiencing mental illness have nowhere to go during the day. Without occupations to engage in, they often report feeling isolated, separated from their community and stigmatized, all of which can cascade into a variety of other health problems. For people with existing health conditions, it becomes increasingly difficult to successfully manage their symptoms and care.

Clubhouses change that. At the center of it all, Agner says, is a community-based, purpose-driven approach.

“Our findings show that Clubhouses improve social connection and functioning,” she says. “They treat mental illness through community, and that community is developed through occupation.”

The model is relevant both for national efforts to reduce isolation and to treat mental illness, and it does so with a focus on occupation — what people actually do to occupy their time during the course of a day.

Included with the report is a modifiable, multimedia slide deck to help Clubhouses translate research into advocacy. Because it’s customizable, the slide deck can also highlight the personal journeys of Clubhouse members like Holton.

“It’s a way of repackaging this knowledge and leveraging it so that Clubhouses and their members can make actual impacts with it,” Agner says.

Moving the needle

Knowledge mobilization, sometimes shortened to “KMb,” describes the nonlinear, flexible process of knowledge generation, uptake and impact. The term is a rebuke to more traditional concepts portraying a linear, unidirectional “dissemination” of research flowing out of the ivory towers of academia.

To help conceptualize KMb, a team of USC Chan faculty developed a new visual model specific to occupational science and occupational therapy. It includes a four-phase process of generating, spreading, grasping and using knowledge, all of which is centered around stakeholders’ shared priority(ies). The phases interact in dynamic, fluid and unexpected ways, and yield impacts which can ripple within the contexts of people’s everyday lives.

Knowledge mobilization means getting research into the hands of people who can use it, including those making decisions about where tax dollars should go for different types of health services.

—Joy Agner

Agner’s work is a prime example of real-world knowledge mobilization — finding creative ways of driving evidence into action for those whose lives might actually benefit from it. Since being publicly released in February 2023, the report and slide deck have been accessed by Clubhouse members, staff and advocates in 33 states and 21 countries.

“Knowledge mobilization means getting research into the hands of people who can use it, including those making decisions about where tax dollars should go for different types of health services,” she says. “We also need to think creatively about how we can support this kind of work on a systems level, at USC and other places.”

Agner hopes that putting rigorous research into the community work that Clubhouses are doing actually moves the needle on funding. California’s Medicaid program, Medi-Cal, has proposed supporting Clubhouses in California through BH-CONNECT, a demonstration project that began in 2023 aimed at improving care of Medi-Cal members with significant behavioral health needs. At the federal level, U.S. House Rep. Ritchie Torres (NY-15) created the Congressional Clubhouse Caucus to advocate scaling up the Clubhouse Model nationwide. Taken together, reducing social isolation, raising mental health visibility and moving towards community drivers of health signal shifting public consciousness and attitudes, Agner says.

“People are looking at alternative models, knowing that a purely biomedical model is not working.”

Product development partners

The approach that Agner and her USC Chan occupational therapy students took in partnership with Clubhouse International was fundamental to their success, says Lee Kellogg, a program officer with the non-profit. By working with Clubhouse International’s research committee to solicit feedback and generate ideas, the relevant needs of all partners were woven into both the process and the final products.

“It’s really giving Clubhouses tools to speak more confidently and more articulately to their stakeholders,” Kellogg says. “Member stories resonate with stakeholders but they also need to see the evidence that Clubhouses work to get behind the funding, which makes the Clubhouse Impact Report a really valuable tool.”

Tying peer-reviewed data to members’ own stories can make them even more powerful, says Patricia O’Brien, with Clubhouse Coalition California.

“Joy [Agner] has an amazing level of insight and vision — she understood how people were going to need to use this material, and distilled it down to a level where really everyone can use it,” O’Brien says.

In the future, Agner is looking to gather more research ideas from the community and from her own work. Questions highlighted by members and staff focus on pinpointing factors that influence a Clubhouse’s success; how Clubhouse services influence housing outcomes; and the effects of Clubhouse engagement on caregivers, family and the broader community.

For Holton, the resources offered by her Clubhouse are vast: educational support, employment support, a culinary unit, phone answering and assistance with banking and money management. All of it, she adds, is designed to meet real needs within the community. For example, if a member is stuffing envelopes with papers, it’s not just to stay busy, it’s to send newsletters to friends and colleagues about the great things happening at that Clubhouse. In the end, she says, the occupation-centric aspect is what makes the Clubhouse Model unique. It’s also making a difference — Holton has not been hospitalized since she started coming to the Clubhouse.

“It’s meaningful work — it’s important, it’s not busy work,” Holton says. “And while doing that, I’m increasing my connections; I’m increasing opportunities to build meaningful relationships; I’m building skills; I’m having a sense of purpose — a reason to get out of bed.”

To access Transforming Lives: Clubhouse Impact Report, visit clubhouse-intl.org/impact-report.

⋯