Narrating Autism, Elopement and Wandering in Los Angeles

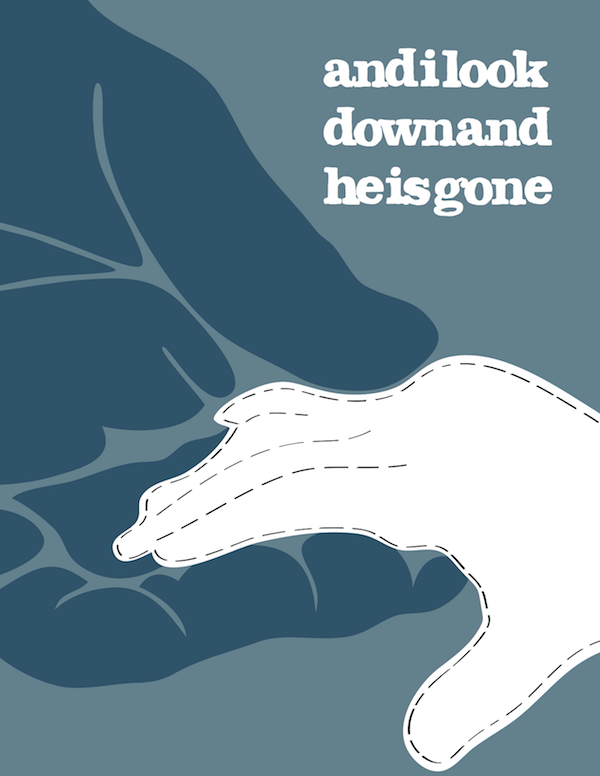

“We were going into the arcade and he was right beside me,” says Noreen, whose five-year-old son, Daniel, has autism. But in a split-second, the family’s time together at a Southern California amusement park turned to crisis. “And I look down and he is gone,” Noreen remembers.

(Editor’s note: to protect confidentiality all names have been changed to pseudonyms.)

Relying on her ability to understand and anticipate her son’s actions and experiences — ‘what would Daniel be doing?’ — Noreen backtracks to the family vehicle in the vast parking lot. Approaching the car, she spots two little feet peeking from behind a tire. “I found him in the parking lot by the car,” she recalls, “like, ‘I’m ready to go’.”

Crisis averted, at least temporarily. A month after the amusement park incident, Daniel, still dressed in his pajamas, quietly walked out of the front door of the family’s home. A stranger driving by called police after pulling Daniel away from a busy intersection, oblivious to the traffic and pedestrian crossing signals, just as he was about to cross.

Such stories are probably familiar to parents of children diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. ‘Wandering’ or ‘elopement,’ the generic clinical terms used to describe a child’s sudden absence from controlled environments without adult supervision, is a behavior recently identified as common in children with autism. A 2011 national survey of parents of children with autism conducted by the Interactive Treatment Network (IAN), an autism registry project of the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore, found that almost half of all children with autism have wandered away from their home or school, a behavior often described by family members as ‘running,’ ‘bolting’ or ‘darting.’

Because the children have no physical features distinguishing them from their typically developing peers, strangers may not realize anything is wrong when seeing a child with autism walk alone. Combined with the social and communication deficits characteristic of autism, which could prevent a child asking a stranger for help, such episodes may turn especially dangerous.

This problem of ‘wandering’ and ‘elopement’ is explored by Assistant Professor Olga Solomon and Professor Mary Lawlor in their article recently published in the journal Social Science & Medicine.1 The data analyzed in the article are part of a larger, comprehensive set of digital video and audio data that provides an in-depth view on the experiences of African American families of their children’s autism diagnoses, interventions and services in Los Angeles County.

The data has been collected for a mixed methods urban ethnographic project, ‘Autism in Urban Context: Linking Heterogeneity with Health and Service Disparities,’ funded by the National Institute Mental Health (R01MH089474, 2009-2012) on which Solomon has served as Principal Investigator.

In addition to Solomon and Lawlor, Professor Sharon Cermak, another faculty member in the USC Division of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy, participated in the project. The interdisciplinary research team also included four faculty members from the Keck School of Medicine of USC: Marie Poulsen, professor of clinical pediatrics; Thomas Valente, professor of preventive medicine; Marian Williams, assistant professor of clinical pediatrics; and Larry Yin, assistant professor of clinical pediatrics and medical director of the Boone Fetter Clinic at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

To better understand the problem of elopement and wandering from families’ perspectives, Solomon and Lawlor analyzed ethnographic, narrative-based interviews with mothers of African American children ages 4-10 who have an autism diagnosis. Of 23 families who participated in the study, nine shared stories of elopement and wandering with the research team during the data collection period.

As part of the larger Autism in Urban Context project, the research team also conducted in-person observations, collected video recordings of the children’s healthcare visits with clinicians and interviewed additional family members, friends and service providers, including occupational therapists. By applying qualitative analysis techniques based upon narrative, phenomenological and interpretive approaches, the researchers identified several themes within and across the families’ data.

Solomon and Lawlor found that some mothers often feel isolated and unprepared due to a lack of professional advice about the problem, similar to the IAN’s finding that families rarely receive advice from practitioners about wandering, even after an instance has occurred. Services that might mitigate elopement and wandering were likely to be absent from children’s treatment plans. Other mothers described facing an uphill battle with public agencies that authorize or deny services when advocating on behalf of their child who has a tendency to wander.

Solomon and Lawlor’s findings bring to light many complex issues located at the intersections of autistic symptomatology, healthcare and human services delivery, inequities in access to these services experienced by many African American families, personal safety, society’s responsibility, and family and community life in urban environments. They hope their research becomes a step toward helping families and clinicians better understand one another in an effort to develop care plans and programs that are more considerate of, and responsive to, children’s and family’s needs. By listening to, and learning from, the mothers of children with autism, the very people who best understand the motivations and needs of their children, this research can empower families, clinicians and agencies to develop and deliver more individualized, comprehensive and family-centered services in the near future.

The study also points to an urgent need to understand elopement and wandering not as only the family’s problem and responsibility, but as an issue that requires family-centered approaches throughout educational, healthcare and human services systems.

“What is especially evident from our data,” Solomon said, “is that this is a problem not only for the families in our study but for others involved in caring, educating and providing services for the children — their teachers, their healthcare providers, the administrators who authorize their services and interventions, the law enforcement personnel who are called during an elopement incident and the community members who act on a moment’s notice to bring the children back to safety.”

“We hope that this research contributes new, useful information to address this complex and urgent problem.”

1 Solomon, O., & Lawlor, M. C. (2013). Social Science & Medicine, 94, 106-114. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.034

⋯