Neighborhood Program’s STAR Power

If you don’t know any doctors or scientists, it can be tough to imagine becoming one yourself. By introducing local high schoolers to research labs on campus, the USC STAR program is one way to get more diversity in science and health fields.

By Eric Lindberg ’07

Jenny Martínez ’09, MA ’10, OTD ’11 speaks up for people who don’t have a voice in the health care system, and ensures they’re treated with dignity.

A scientist and expert in occupational therapy for nearly a decade, Martínez studies how to best care for older adults and people with debilitating injuries. She also passes along her wisdom to the next generation, teaching occupational therapy students how to conduct studies and serve clients with respect.

It might be surprising, then, to hear that she was once a teenager unsure of her place in science. Martínez remembers feeling a little scared, apprehensive and intimidated the first time she entered a research lab on USC’s Health Sciences Campus as a junior in high school. Back then, it all seemed so overwhelming. Lab benches teeming with complicated equipment. Scientists busily buzzing around with an air of knowledge. USC students setting up their experiments with confidence.

Even though she loved science, going to college and pursuing a career in a STEM field felt out of reach for Martínez. Only a few kids from her East Los Angeles neighborhood were in college, let alone studying science or engineering.

But stepping into the USC lab as a high school student helped her recognize her own potential and confirmed her hope: She had the intelligence and drive to become a scientist.

“The experience set me on a clear path to success,” Martínez says. “It helped me understand what I was capable of and connected me to supportive mentors who had gone to college for science and engineering themselves. It gave me role models.”

Martínez thrived in USC’s Science, Technology and Research (STAR) program, which pairs students from Francisco Bravo Medical Magnet High School with USC faculty members to work on research. It’s one of dozens of community projects that benefit from the USC Good Neighbors Campaign.

Now in its 25th year, the USC Good Neighbors Campaign has raised more than $25 million, largely through donations by USC faculty and staff members. These funds provide hundreds of grants to local community programs. When the campaign began 25 years ago, it raised $185,000 and funded nine grants. Last year’s campaign raised $1.4 million and funded 50 programs in communities like Boyle Heights, El Sereno and Lincoln Heights that surround the Health Sciences Campus.

Campaign helps community programs thrive

For Martínez, her experiences in the STAR program encouraged her to follow her passion for science. Along with a bachelor’s degree in health promotion and disease prevention studies from the Keck School of Medicine of USC, she earned her bachelor’s, master’s and clinical doctoral degrees in occupational therapy from the USC Chan Division, where she later served as a faculty member for five years. She is now an associate professor at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

Martínez looks back with gratitude for the encouragement and support she received as a young aspiring scientist unsure of how to turn her dreams into reality.

“There are many systemic barriers to college access and success, even when the school is next door,” she says. “Programs like these increase diversity in higher education and expand access to equitable, valuable experiences for students.”

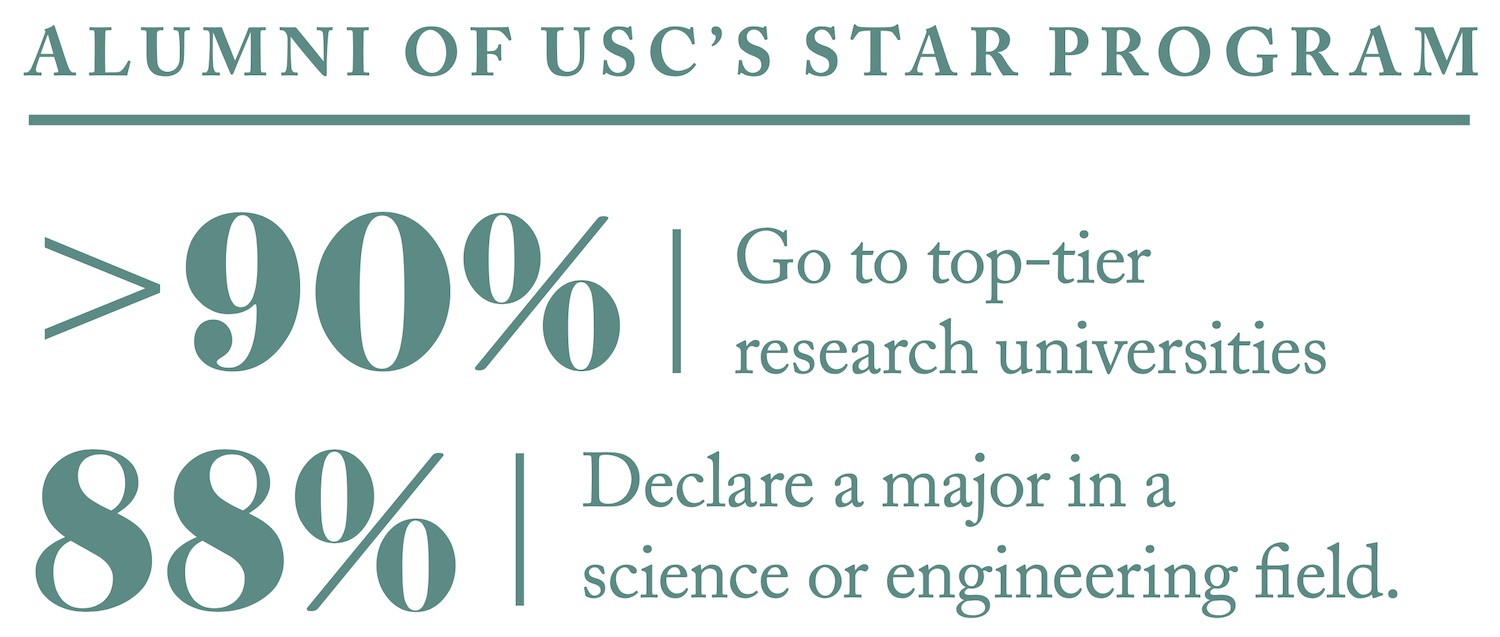

Virtually all alumni of USC’s STAR program attend college. More than 90 percent go to top-tier research universities, and 88 percent declare a major in a science or engineering field.

The program is not only a pipeline to increasing diversity in health and science professions (according to the National Center for Education Statistics, 96 percent of Bravo Medical Magnet’s students come from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups), it can forever change the trajectory of students’ educational outcomes.

“The money raised can provide access to life- changing upward economic and social mobility for members of the local community,” Martínez says.

Hands-on learning with USC faculty

USC researcher Daryl Davies has witnessed the remarkable success of the program since the early 1990s. He started in STAR as a mentor when he was a doctoral student, then continued when he joined the USC research faculty. Now he directs the program. Dozens of high school students, including Martínez, have gained research skills in his lab at the USC School of Pharmacy, where he also serves as associate dean for undergraduate education.

“They get hands-on lab experience with real science projects — doing funded research to develop new molecules, discover groundbreaking technologies to treat diseases, engineer new devices, you name it,” Davies says. “They are involved in cutting-edge research as high school students and become junior scientists.”

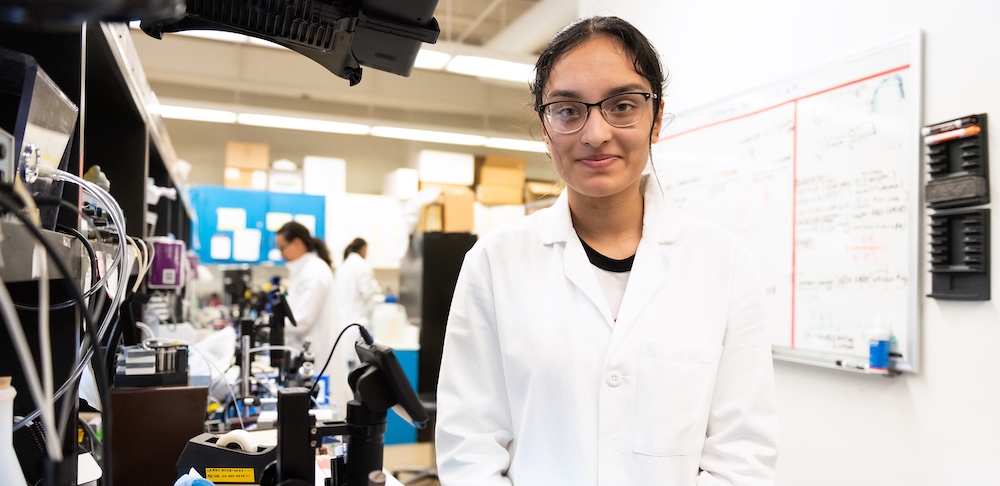

Nirali Patel is one of those scientists-in- training. The 16-year-old joined Davies’ lab this past summer to help with research into new treatments for alcohol use disorders. With the guidance of her mentor, PhD candidate Larry Rodriguez, she’s learning about biochemistry, molecular biology and more.

“We puncture oocytes — they are frog eggs — and inject them with a certain kind of RNA,” Patel says. “We try to activate receptors within them that can regulate the effects of alcohol. So, in other words, they can alter our tendency to drink alcohol.”

An aspiring pediatrician, Patel plans to study biology in college. She hopes her hands-on experience in the lab will give her an edge in the application process and jumpstart her undergraduate career. She has good reason to think it will: Her brother completed the STAR program in 2015, also in Davies’ lab. He recently earned his bachelor’s degree at UCLA in microbiology.

“[My brother] always told me how much he loved working there and being part of something bigger that could help people,” Patel said. “Ever since I found out about it, I wanted to get into a lab there.”

Bonding over college admissions advice

Patel lives in Gardena, Calif., and each day she takes a long bus ride to Bravo, near the Health Sciences Campus in East L.A. She spends three or four afternoons a week in Davies’ lab, often staying until 5 p.m. or later, until her mom picks her up afterwards. But she says it’s worth the extra time and energy.

“I like forming networks with the other people there,” she says. “I’m usually a shy person, but I’ve found close friends with the people in my lab, the other USC students. They always give me advice about college applications, because they are almost due.”

STAR participants get a chance to bond with other lab members during a full-time summer internship for six weeks before their senior year of high school. They also receive a stipend for their work, along with funding to create and present research posters, and celebrate with their families at an awards banquet when they graduate from the program. Davies says those perks would be impossible without the support of the Good Neighbors Campaign grant.

Martínez says that the stipend enables many students from lower-income backgrounds — students who might otherwise have to get a job to help support their families or save money for college — to take the valuable internship during high school.

“Spending that time on a learning experience crucial to my success in college was an investment in my future.”

⋯