The Longest Year

Reflections on the frontline pandemic experience from a hospital-based occupational therapist.

By Carnie Lewis ’17, MA ’18, OTD ’19

Assistant Professor of Clinical Occupational Therapy

Listen to Lewis read this article.

SPRING 2020

I wake up, make my coffee, get changed, brush my teeth and head straight to work. I’m not a morning person — it’s a wonder how I ended up in a job that starts at 7 a.m. every day.

Just as the caffeine kicks in, I enter the occupational therapy office on the third floor at Keck Hospital of USC. Much like any other morning, several people are crowded around the schedule board, assessing where they can fit in another patient within the timetable of OTs who are working today. Before I officially start my work day, I take a quick glance at the news (I am now awake enough to process basic words).

We’ve been hearing about the novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China, for a couple of months now, but it still sounds like a fictitious character. I laugh with my colleagues beside me in our cramped office, as we share jokes and tell a few stories. At some point, a colleague speculates that AOTA’s annual conference will be canceled. I don’t see that happening — it just seems so extreme at this point in time. After all, I had just flown back from Las Vegas for OTAC’s spring conference, and that event was a hit, despite skittish concerns about random outbreaks in major cities around the U.S.

Over the next few days, my morning routine’s the same, but the news is reporting an increasing number of positive cases around the nation. The hospital starts to feel eerie as we think about our own personal risks.

It’s mid-morning by the time I get a text to stop treating patients ASAP and head straight for a meeting room. I’m not alone. There are 20 other physical, speech and occupational therapists in the room, and we’re each given a surgical mask and told to sit six feet apart. Immediately, I know what’s going on. Despite my positive outlook that has kept me blissfully ignorant of dire details in the news the past few weeks, I am immediately sobered. COVID-19 has arrived at the hospital, and we have already been exposed.

My way of life changes quickly. The stay-at-home order gives me time to engage in the meaningful occupations that I’ve neglected since high school. I bake, draw and learn to make ice cream. I reorganize my room three separate times and participate in Zoom call after Zoom call with old friends.

At work, elective surgeries are canceled, as many patients as possible are discharged and medical-surgery units are upgraded to ICU-level units in preparation for the surge we are told is coming. The OT department is put on a staggered schedule so that we can decrease the need for physical presence in the hospital. We now sit six feet apart, wearing surgical masks all the time. Nobody is laughing in the morning. No one is huddled up to analyze the daily schedule board that is now half the size it was just a month ago. As we see the news from New York grow grimmer by the day, our only motto is to be as efficient as possible in order to minimize unnecessary time spent in the hospital environment.

A month goes by, and the fear surrounding the chaos grows. Every minute of every day contains new information from the hospital, the news and the scientific community. It feels like whatever sense I have just gained is quickly taken from me. Every night I get home to read COVID updates, and every morning I wake up to new announcements that contradict what I just read the night before. Strangely, I find that working directly with patients seems to be the one thing that doesn’t dramatically change from day to day. But I’d be lying if I said I was comfortable being in the hospital, where it felt like no one was truly safe.

It’s not until late April when I am pulled onto the COVID-19 clinical care team.

SUMMER 2020

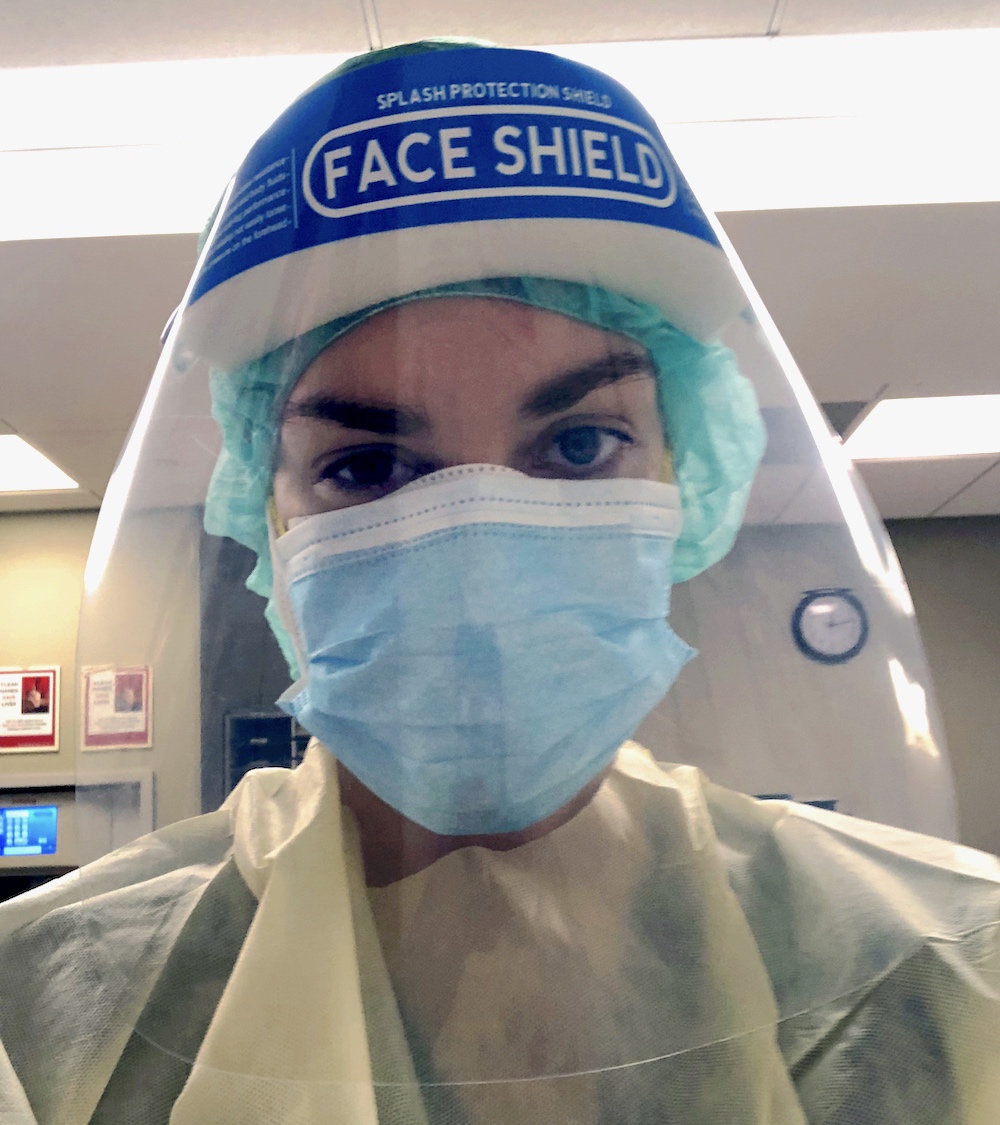

I take a deep breath and go through the motions of donning my PPE, my personal protective equipment. Like a mantra, I repeat the steps over and over in my head to make sure I do it correctly:

Wash hands.

New hair net and clean shoe covers.

Yellow gown.

N95 mask.

Surgical mask over N95.

Face shield over both of those.

Sanitize hands.

Don gloves.

Finally, I ask a nurse to tape up the back of my contact gown. It’s hard to breathe, but I’m not sure why. Is it because I’m sweating under this mass of paper and plastic? Or is it because, even though I’m covered head to toe in PPE, I still fear exposure to COVID-19? It’s early summer, but it seems we still know very little about the virus that’s getting transmitted at higher rates every day.

The suction of air gusts loudly as I open the vacuum-sealed door to the room of my first patient of the day. Jason is a 37-year-old with cystic fibrosis and HIV who recently tested positive for COVID-19. Jason is already receiving six liters of supplemental oxygen through an oxymizer, a thick plastic tube that wraps around his head and pushes concentrated oxygen into his nose in an attempt to make up for what his lungs are not able to absorb. Yet, even with this high level of oxygen, I’m told by his nurse that Jason continues experiencing rapid decreases in his blood-oxygen levels upon minor movements.

An awful feeling settles in my gut as I walk into the room. I introduce myself, my role and go through the basics of testing his vital signs — blood pressure, oxygen saturation within his blood and heart rate. At rest in bed, he’s at 93 percent oxygen while on the oxymizer, which is above the critical 90 percent minimum, with heart rate only slightly elevated at 110 bpm.

He doesn’t demonstrate any increased work of breath or distress, and is very motivated to get out of bed so that he can finally transfer to a commode. Even so, the moment he sits at the edge of the bed, his oxygen drops to 85 percent. He insists he doesn’t feel short of breath despite the desaturation, but is clearly fatigued and working harder in his chest to breathe in and out. The moment he transfers to the commode at bedside, his oxygen levels drop even further, requiring constant vigilance on my part to monitor every symptom and vital sign. I work with him to facilitate slowed and deep breathing through his nose, and decrease the demands of the task in order to improve his oxygenation.

Underneath my gown, gloves, mask, face shield and hair net, I’m sweating. The moisture and heat coming off me starts building up and fogs my face shield. I breathe a sigh of relief when Jason has returned to bed and his oxygen recovers to its pre-activity level.

Every second of the day, Jason’s oxygen saturation is monitored closely via a wireless pulse-oximeter on his finger that transmits the number to a computer at the nurse’s station outside of his room. A mere nine hours after the morning’s occupational therapy treatment, Jason is transferred to the ICU to receive even more concentrated oxygen and monitoring due to a rapid deterioration in his lungs. Nurses and physicians remain on standby to intubate him for possible mechanical ventilation.

After ending the session and repeating the tedious but vital process of taking off my contact gown and gloves and replacing them with new ones, I’m ready to visit my second patient of the day.

I meet John, a 75-year-old who had been transferred from an outside hospital after he tested COVID-19 positive. John has metastatic osteosarcoma, a bone cancer, in his spine, right thigh and lungs. He obtained a fracture from the spine metastases, and any movement gives him significant pain. Despite his age and the fact that cancer is a serious comorbidity, he exhibits no “typical” COVID-19 symptoms. He breathes with adequate oxygen saturation on room air, his heart rate is stable and he doesn’t experience any fatigue, loss of smell or other symptoms that we have come to associate with COVID-19. In fact, John will later be classified as an “asymptomatic” positive case. I evaluate and treat to address his pain, increase his strength and endurance, and teach him how to change basic daily activities in a way that will not risk further spinal fractures, just as I would for my other patients with spine-related oncological diagnoses.

My third patient of the day is Miguel, a 26-year-old with no known comorbidities. He is on the road to recovery, receiving a mere two liters of oxygen through a nasal cannula. Miguel has already left the ICU after being mechanically ventilated for weeks on end. Unfortunately, Miguel also suffered a stroke while in the ICU, which we now know can be a common result of COVID-19 because of its impact on blood coagulation.

Miguel is no longer the same person he was before contracting the virus. He demonstrates hemiplegia, severe paralysis to the right side of his body, and is currently non-verbal because the stroke impaired his memory, executive functioning, motor control and communication skills. Yes, Miguel is a survivor, and he will be recorded by Los Angeles County as “recovered.” But he will still require weeks and months of multidisciplinary rehabilitation.

In my treatment session with Miguel, I focus on neuromuscular retraining of the right side of his body, so that he can sit up at the edge of the bed without falling over. I also work with him to begin using the muscles in his right leg and arm so that one day he can dress, eat, stand and walk without the need for maximum assistance.

Cesar Millan, a nurse from Palm Springs who contracted COVID-19 from one of his own patients, spent 85 days at Providence Saint John’s Health Center in Santa Monica before arriving at Keck Hospital of USC to await a lung transplant.

FALL 2020

The N95 mask imprints lines on my face that last for hours after I take it off, thanks to the dehydration I’ve sustained over the day because I am unable to drink water between treatment sessions. Even though I’m home, showered and done for the day, those lines are a reminder that I am not free of this virus and its impacts on my own body and mind. I can’t help but wonder where the rhyme or reason to this virus is. How does one person remain asymptomatic, while another demonstrates significant disease and impairment?

Data show us that patients with more comorbidities and older age are at a higher risk for fatality and/or serious complications as a result of COVID-19. But it’s hard to feel confident that we can predict anybody’s disease course. It’s hard to feel that I have any sense of understanding or control when each patient presents so differently, and thus require such different approaches to occupational therapy treatment. It’s still so hard to feel safe myself, though I trust the PPE I wear.

The fear that COVID-19 has imposed on society permeates every interaction and movement of my day. Was the 30 seconds that I spent washing my hands between patient rooms enough to clear the virus? Will the cough of a patient spread particles under and around my face shield, onto my face and infect me? Is there a chance that I unknowingly carry the virus and infect someone else?

We’ve been focusing so much on COVID-19’s mortality rate that we often forget that recovered infections can still have lasting symptoms and impairments. I’m relatively young and healthy. Statistically, I am less likely to experience significant disability or mortality. But all I have to do is think back to Miguel’s stroke and be reminded of how severe this virus can be for the young and healthy too.

The hospital still feels so much different than it did in early March. But with time, the novelty of masks disappears. I’m used to sitting six feet apart while reviewing charts. The ebb and flow of cases becomes mundane. At least, that’s what I think, until the third and largest surge hits Los Angeles County after Thanksgiving. I force myself not to check our electronic chart system to calculate the remaining numbers of open beds at Keck Hospital. Unfortunately, it’s all for naught when I receive an email from our CEO with the subject line “HIGH CENSUS ALERT.” We have very few ICU beds left, yet we are one of the handful of facilities in the county that still have any beds available at all. Day by day, the number of employees who test positive grows. Nursing units become understaffed, and our morgue fills up. This surge is by far the scariest one yet, because our hospital system is becoming so overloaded.

WINTER 2020-21

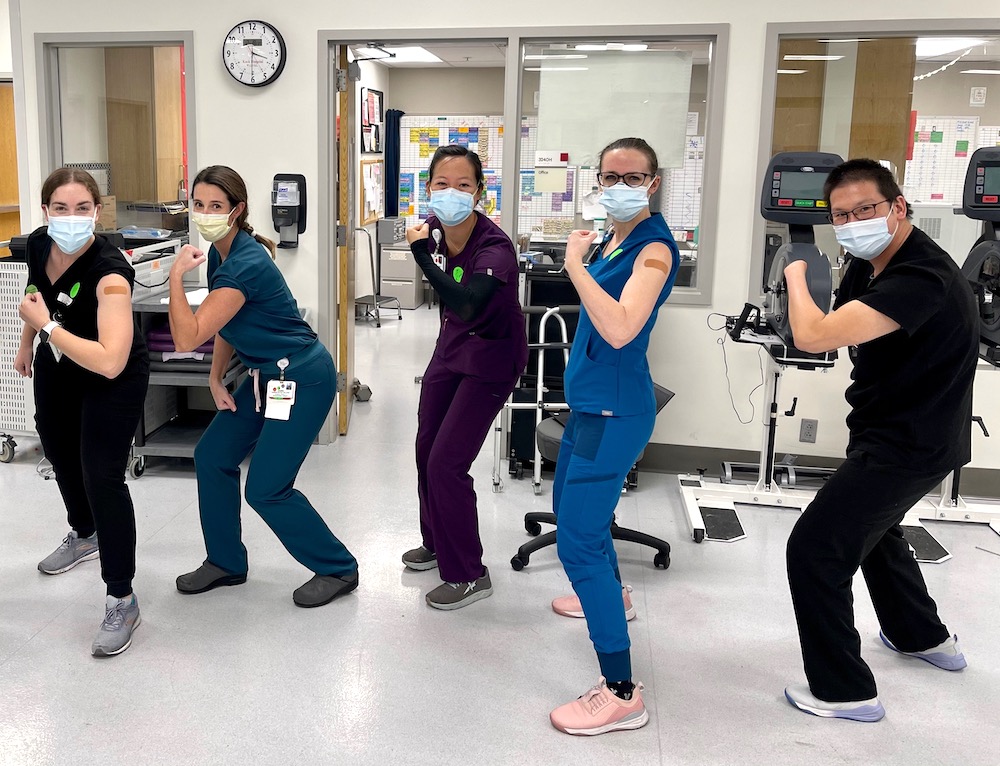

Hope is an emotion I have avoided for the last several months. But today, I am hopeful.

As I feel the sharp prick in my left arm, tears begin welling up in my eyes. I feel a twinge of guilt at giving the impression that I’m in serious pain to the nervous pharmacy student who’s administering my injection. I can’t believe I’m crying, but it also feels like the most natural reaction to have. What’s the normal response to getting the first dose of the vaccine? After having worked for so long on the COVID-19 units and being so stressed about my own safety and the health of those around me, the vaccine feels like a breath of fresh air. It feels like seeing a light at the end of this tunnel, even if it’s still very dim and distant.

From a clinical standpoint, I am confident that occupational therapy care has been critical for the survival and rehabilitation of individuals recovering from COVID-19. For example, I recently had one patient, Susan, whose cardiopulmonary endurance was so low and oxygen needs so high that she could barely sit upright for more than a few minutes without experiencing dangerous drops in blood-oxygen levels. After working with her for a few weeks, we were able to decrease her oxygen requirements and improve her activity tolerance so that she could engage in more than 30 minutes of seated activities. Ultimately, this allowed her to independently complete all of her basic daily activities such as bathing, eating and grooming (an independence that we too often take for granted). With her increased independence, Susan was able to go home with family support, and thus open up a scarce hospital bed for a new patient in need.

Meeting patients at their most vulnerable and frightened moments helps me forget about my own fears — and the horror of the hundreds of thousands who have died from this disease — and to remember that I still have control in this one aspect of helping someone heal. I can utilize my unique lens as an occupational therapist to target whatever aspect of their being, whether socio-emotional, physical, cognitive or values-based, that needs assistance and healing. I was able to work with Jason, John, Miguel and Susan in varying ways that, at the end of the day, contributed to each of their own recoveries. It’s worth the long days and weeks, the exhaustion and the dehydration under the N95s, when I see a patient successfully discharged.

Nevertheless, despite the hope from the vaccine, I know this pandemic is far from over. I will treat many more Jasons, Johns, Miguels and Susans, just as I will treat more patients who do not survive. At this point, I’ve lost so many of my patients from COVID-19 that I’ve stopped counting. Some I had already known from previous hospital admissions, when I had treated them after a liver transplant or a bladder cancer resection. To my mind, they had already survived their health crisis of liver failure or cancer. To watch them succumb to this virus a few months later back at Keck Hospital fills me with grief and rage. It’s one of the reasons I get so incredibly upset when I see people unmasked, or being blasé about stay-at-home orders. Lives are at stake, and we have the responsibility to do everything possible to protect them.

Being a frontline occupational therapist during COVID-19 has been one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do. Although I’m still a younger therapist, I imagine that working on the COVID units will forever be the greatest challenge experienced in my career. Despite the difficulties, there are so many things to be thankful for: adequate PPE, colleagues who support me and FaceTimes with my family who live more than 9,000 miles away in Australia.

I look forward to the day when this pandemic is over, or at least, to the day when it’s controlled enough to not have to live in this state of constant unknown. I am hopeful that the vaccine will provide a measure of control, even though its population-wide effects are still months away.

Until then, I will continue doing my part to help individuals in our community heal. As I do my part, I beg of everyone else to do theirs. I don’t have the luxury of staying at home, but if you are able to, please continue doing so. Stay safe, abide by social distancing, wear a mask and listen to public health officials. Let’s flatten this curve, reduce the surge and work to ensure we keep as many people as we can safe and healthy.

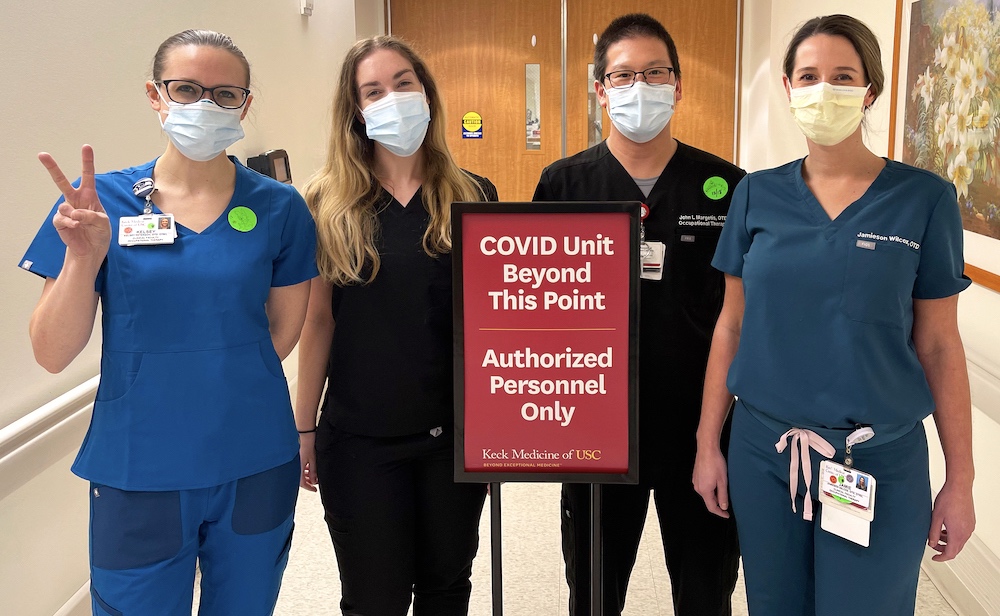

Faculty members and COVID providers at Keck Hospital of USC (from left to right) Carnie Lewis, Jamie Wilcox, Jennifer Chan, Kelsey Peterson and John Margetis.

⋯