Tipping the Scales

In 1980, 7 percent of American children were obese. In 2012, nearly one-fifth were. Reversing our nation’s prevalence of childhood obesity will require more than health guru anecdotes, dieting dos and don’ts and slick slogans from preachy — albeit well-intentioned — publicity campaigns. Read how the clinical research of one faculty member at the USC Division of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy aims to tip the scales toward a healthier, happier future for our children.

By Mike McNulty ’06, MA ’09, OTD ’10

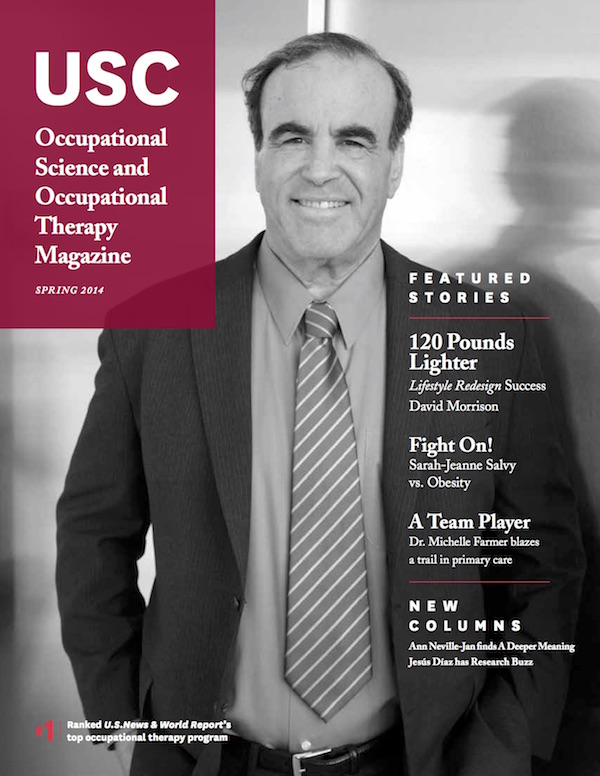

Associate Research Professor Sarah-Jeanne Salvy joined the faculty of the USC Division of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy in September 2013. A fellow of the USC Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research, she is also an adjunct behavioral and social scientist at the RAND Corporation (Santa Monica, Calif.) and was previously an Associate Professor of Pediatrics at SUNY Buffalo (New York). A native of Quebec, Salvy received her PhD degree in Child Clinical and Pediatric Psychology from the University of Quebec at Montreal. She is interviewed about her work and career by the division’s Director of External Relations Mike McNulty.

Can you give our readers an overview of the general aims and themes of your research?

My entire research focuses on obesity, especially childhood obesity, and how social factors can either promote healthy behaviors or reinforce obesogenic behaviors. There has been a lot of research on the influence of physical environments on obesity, but now we’re seeing more research on the impact of the social environment.

What specific projects are you focused on at the moment?

Right now, my “baby” is to integrate a childhood obesity prevention curriculum within the structure of an existing home-visitation program. It’s an incredible model of service delivery: home visitors deliver the intervention in the home every week, it’s widespread across the United States and is used internationally in Europe and Canada. It’s such a great infrastructure, but the home-visitation model has never been systematically used to target obesity. And this is the population most at-risk. More than 39 percent of children involved in federally funded programs are overweight or obese. My research is looking at integrating the evidence-based nutrition and activity components within the structure of the home-visitation program. It seems like such an incredible opportunity.

In the face of the powerful economic, emotional, cultural and commercial forces surrounding food and eating behaviors, how much of an impact can research-based clinical interventions truly make on stopping the obesity epidemic?

Recent research suggests that childhood obesity is actually plateauing, and that childhood obesity is not getting worse anymore. However, 30 percent of children are still overweight or obese; I say that that’s still an issue. If one in three kids at age 5 is overweight, and if we can decrease that prevalence by even a very small percentage, we’re talking about very big potential cost savings in the long run. Twenty percent of health care costs go to obesity-related diseases. So if we focus our efforts on at-risk populations, we can remove a significant proportion of the financial weight, no pun intended.

The Institute of Medicine put out a recent recommendation about how the future of population-level health will require partnerships that mix or combine service delivery systems and clinical interventions. In other words, by combining practices and delivery systems that have been shown to be evidence-based, to focus on families most at risk, we can have the biggest impact on improving health and quality of life and decreasing the long-term financial burden for society as a whole.

Twenty cents of every dollar spent on health care goes to obesity-related diseases. (Congressional Budget Office)

What motivated you to pursue a career in clinical psychology research, specifically research on interventions for feeding and eating disorders and the connection to obesity?

There was never a single moment but kind of a series of serendipitous events, which brought my career to where it is today. Even though I’m now focusing on obesity I started at the other end of the spectrum, working with children who have feeding or eating disorders. During my clinical internships with children with feeding disorders, I started noticing the power of social interactions between the feeder and the feed-ee, and how a successful therapist can reshape a dysfunctional feeding relationship, rebuilding it from scratch.

That’s a question not just for people with feeding dysfunction but for normal people too: How are other people influencing your own “typical” eating habits? For example, if you go out to a restaurant with a group of your colleagues and nobody is ordering dessert, will you still order dessert?

So at the University at Buffalo, I translated this model to obesity: how social contingencies influence “how much” and “what” kids eat, and their choice of activities. At RAND Corporation, I began translating these basic findings to applications that have public health implications, asking, “how can we take basic lab studies and turn them into something with a greater impact?” If obesity is becoming the norm, if a large proportion of the population is now overweight and overeats, what’s the impact on the incidence and prevalence of obesity? And what interventions will have the biggest impact in terms of scalability? Those are the type of questions my research here at USC hopes to answer.

Occupational science, by design, is a very interdisciplinary endeavor. What does clinical psychology uniquely contribute to the broader field?

My research focuses on how people around you influence how you occupy your time throughout the day. I’m asking, “how does allocation of behavior influence weight?” It’s very similar to the classical definition of occupational science that Dr. Florence Clark would give: studying how the choices you make, how you spend your time and how you occupy your time directly influence your health.

What impact does, or will, your research have on the 40 percent of U.S. occupational therapy practitioners who work with children age 0-21?

Even though I’m now more focused on academia and research, I’m still a clinical psychologist, bringing the experiment into the real world. I’ve worked with OTs since the beginning of my career. I’ve actually worked with OTs on behavioral interventions for feeding and eating disorders. I’ve worked in hospitals and as part of multidisciplinary teams, so I’ve always felt like a member of the family.

Though your career is still relatively new, you have already been principal or co-principal investigator on two research projects funded by multimillion-dollar NIH grants. What’s the secret to your success?

I don’t think there’s any secret right now; it’s tough to get funding for everybody! I would say that I’m very stubborn, and by stubborn I mean persistent in the face of rejection. I will submit a grant proposal six times if I have to. It’s not like it used to be. Now, you have to accept that you’re not going to get it funded the first time, but if I strongly believe that I have a good idea that is impactful, then I’m going to pursue it.

So you submit, you get feedback, you revise and you resubmit. The biggest enemy is disappointment and getting discouraged. It’s easy to give up right now and say, “forget it, I’m going to open up a bakery or something!” But any successful researcher has to be a bit naïve, or, maybe not naïve, but hopelessly optimistic.

Lastly, what’s your favorite thing about living in Los Angeles? Please don’t say the bakeries!

It would have to be the diversity of everything, in every sense of the word: the scenery, the neighborhoods, the vegetation, the food. Feeling like there are multiple cities all within a single city.

⋯