Experimental Soccer and the Good Life

In a blog from her new textbook, Moral Laboratories: Family Peril and the Struggle for a Good Life, USC Chan Professor Cheryl Mattingly explores suffering and moral striving

By Cheryl Mattingly

Editor’s Note: Cheryl Mattingly is a USC Chan professor with a joint appointment at USC Dornsife’s department of anthropology. Parts of this article originally appeared as a post on the blog of the University of California Press, the publisher of Mattingly’s latest book, Moral Laboratories: Family Peril and the Struggle for a Good Life. It is Mattingly’s second book drawing upon Boundary Crossing, a 15-year longitudinal ethnographic research program beginning in 1997 of African-American families raising children with a range of significant chronic illnesses and disabilities as well as the clinicians who served them. Overseen by Mattingly and Professor Mary Lawlor and funded through multiple Maternal and Child Health Bureau and National Institutes of Health grants totaling more than $5 million, its research aims were to identify and describe how families contribute to the production of culturally responsive care and to reveal the strategies families and practitioners enact to establish commonalities and bridge differences to partner together effectively.

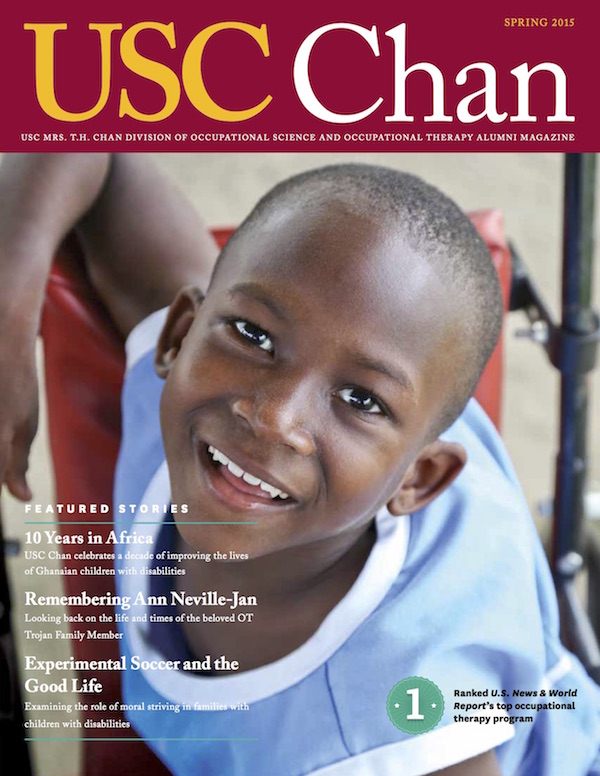

It could be one of any thousands of soccer fields scattered throughout America. Grade-school children in their uniforms running up and down the grass, shouting to one another as their parents cheer them on. It is an ordinary Saturday afternoon event repeated in countless towns and cities across the United States. Except that in the center of this field, as screaming children fly by, is a boy in a wheelchair being madly propelled by another boy as, together, they too head in the direction of the ball.

His father and mother stand on the sidelines watching the action. The boy’s parents, Tanya and Frank, have three children — two girls and a son, Andy, who is their oldest. Andy was born with an extremely severe case of cerebral palsy, which not only leaves him physically disabled but very cognitively impaired as well.

Tanya is one of those mothers determined to fight for her son’s rights to good schooling, and she is fierce in her determination to stand up to school board members, principals and other public officials in order to get good care for her son. “It’s my Jamaican blood,” she laughs, justifying her willingness to battle authorities.

But she credits her husband, Frank, for opening her eyes to her son’s capability to participate in everyday children’s activities that she would have shielded him from otherwise. Her husband is an athlete, a natural at many sports, and he maintains that a son — his son — should love sports as much as he does.

Frank decided that he should get Andy involved with the local children’s soccer team. Tanya, however, was terrified and absolutely refused; they fought about this for several years. But finally Frank prevailed, and Tanya let her son go out onto the field.

During one of the games, just as she feared, Andy’s wheelchair was accidentally knocked over and he toppled to the ground. But, to her great surprise, he didn’t even act frightened.

This is a story Tanya has told more than once. It moves her every time; catching her up short, this realization that despite her determination to make others view her son as capable, she herself underestimated him and the community surrounding him.

I came to know Tanya and Frank as part of Boundary Crossing, a long-term research study among African American families in Los Angeles raising children with significant illnesses and disabilities. I have been repeatedly struck by how often parents respond to the suffering of their children by trying to transform not only themselves but also the social and material spaces in which they live.

Parents like Tanya struggle to cultivate more morally worthy characteristics — to become “better” parents — in the face of immense demands illness and suffering can bring; to “step up to the plate,” as one father put it, in order to care for their medically fragile children. These practices of care are undertaken in circumstances that are always fraught and sometimes seem impossible spaces in which to find any “best good” worth acting upon. Parents may even carry out moral experiments, such as the re-invention of a local soccer game, as part of raising their children.

How might we represent and theorize moral experience, including its experimental side? Anthropologists have relied upon a host of powerful intellectual voices to give analytic depth to accounts of suffering, especially as connected to widely (even globally) dispersed institutional forms of governance, knowledge generation and control.

But what about the aspirational aspects of life — of moral striving? What truths might we uncover when we pay attention to not only suffering but also to people’s attempts at realizing good lives even in unpromising circumstances? How might we look at the inventive qualities of moral striving? What analytic frameworks might be useful?

My focus on meaningful activity and the good life can be traced back to the late 1980s when I was asked by the American Occupational Therapy Foundation to carry out a study of the clinical reasoning of occupational therapists, a study which resulted in the 1993 book Clinical Reasoning: Forms of Inquiry in a Therapeutic Practice co-authored with Maureen Fleming.

In my new book, Moral Laboratories: Family Peril and the Struggle for a Good Life, I outline a virtue ethics approach, drawn from moral philosophy, to explore the promises and perils of moral becoming as connected to family practices of care.

These themes may appeal to occupational therapists working in a range of practice areas where “partnering up” with family caregivers is especially important. Occupational therapists, more than many other health care providers, are concerned with what is of significance to the people they serve. This is, of course, also a concern for parents raising children who have disabilities that might preclude many “ordinary” childhood experiences, parents who too want their children to participate in important child activities and be part of the daily rounds of family life.

Purchase a copy of Moral Laboratories: Family Peril and the Struggle for a Good Life.

⋯