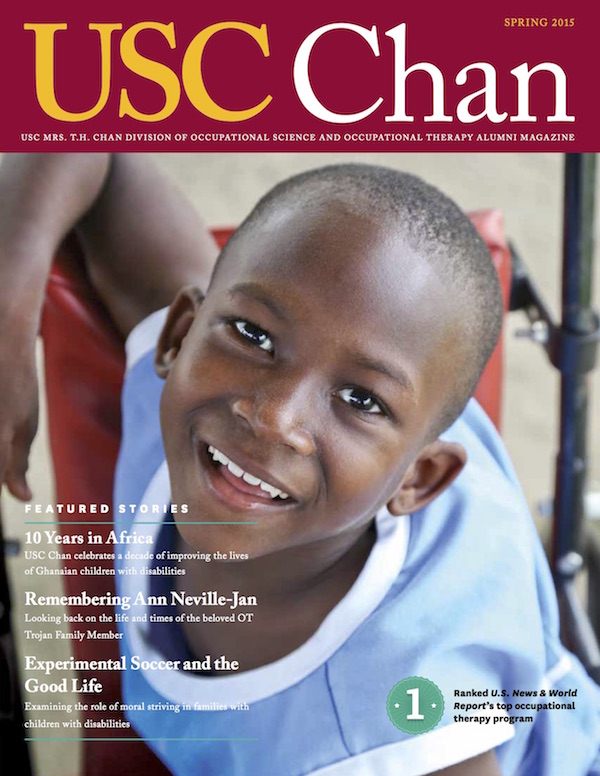

10 Years in Africa

2015 marks the 10th anniversary of the leadership externship that has taken more than 200 USC Chan students to Africa’s West Coast.

By Jamie Wetherbe MA ’04 (with photos by Heather Dingess DPT ’09)

Bonnie Nakasuji ’74, MA ’94, OTD ’08 first went to Ghana in 2003 with a simple mission. She wanted to match patients with wheelchairs.

Only two years later — thanks to her passion for OT and a good deal on airfare — Nakasuji returned to Ghana with 10 USC Chan students in tow to help adults and children with disabilities.

During the past decade, Nakasuji, an adjunct associate professor at USC Chan who coordinates the division’s leadership externship to Ghana, has ushered 232 USC OT students to Ghana, taking on some 50 duties from arranging air travel to lecturing at universities.

“It’s just been an amazing journey,” Nakasuji says. “When a student has an opportunity to give professionally, it’s really rewarding.”

“While in Ghana, I learned the importance of lifting my eyes from my own agenda to see the beautiful and fluid blending of various cultures, perceptions, values and personal characteristics. I have since learned the professional importance of stepping back and taking on a position of humility instead of immediately assuming an ‘expert’ role when working with my clients.”

— Natalie Pierson ’12, MA ’13

“I have always been interested in international work, and I wanted to do something bigger,” says Erin O’Donnell MA ’13, OTD ’14, who first traveled to Ghana in 2013 as a student and returned the following year as a practicing occupational therapist. “I’m planning on going back forever.”

Part of a Movement

Traditionally, Ghanaian society has held an attitude that those with disabilities are “useless,” Nakasuji says. It’s even more pronounced in small villages.

“People believe that those with disabilities are cursed, so families who have children with disabilities throw them away,” she says. “They have to get rid of the curse; they don’t want it to permeate the family or the village.”

The Stigma of Disability

According to traditional Ghanaian religious thought, people with disabilities are “cursed” as a result of the family’s sinful behavior. To avoid the stigma, families often abandon their disabled children. Enter Mephibosheth Training Center. This boarding school for children with special needs opened its doors in March 2005 to take in these “throw-away” children — ages 4 to 22 — and educate them to contribute to society in meaningful ways. Since USC Chan began working with Mephibosheth a decade ago, 232 occupational therapy students have had service-learning experiences at the special needs school.

Social centricity in an African village requires that each person contribute to the group’s livelihood.

“Some people in Ghana think people with disabilities can’t do anything, so they’re not only cursed, [they’re] worthless,” Nakasuji explains.

Many Ghanaian children have a story of survival, Nakasuji says, including a boy she met who remembers his father taking him to the bush and leaving him to die.

“Infanticide is alive and well in Ghana,” she says. “But I want to emphasize this attitude is changing.”

In fact, advocacy for people with disabilities in Ghana took a giant leap forward in 2006 when the disability rights law passed, which protects people with disabilities from discrimination, exclusion and abusive or degrading treatment.

“The country has really changed in the last few years, with more locally run and locally funded programs,” says Mariko Yamazaki MA ’10, OTD ’11, who first went to Ghana as a student and now co-coordinates USC’s leadership externship.

Eight years ago, the University of Winneba in central Ghana launched a community-based rehabilitation (CBR) program to empower those with disabilities. As part of their externship, USC OT students are paired with CBR students for a leadership activity.

OT students join CBR students at a hospital, village or school, and together they work providing support and advocacy for patients, often with little or no money or equipment.

“These are families that don’t have a therapy clinic down the street; they might not even have access to running water,” Yamazaki says. “We have to make recommendations on what’s realistic knowing that we won’t be back in a month to follow up.”

The most common disabilities OT students encounter in Ghana are cerebral palsy and polio, Nakasuji says.

“Many people don’t have access to the polio vaccine or refuse to vaccinate because they believe it causes impotence in boys,” she explains.

USC OT students have also worked with children with a range of disabilities at the Mephibosheth Training Center since the day it opened in 2005.

The goal of the boarding school, which takes its name from the only disabled child mentioned in the Bible, is to train children to take on one of three vocations — sandal-making, sewing or carpentry. “If they learn a skill, they can contribute to village life and they won’t be mistreated or thrown away,” Nakasuji says. “A sandal-maker, seamstress and carpenter are considered really good, middle-class jobs.”

OT students present simple, fun activities related to sewing, leatherwork or woodworking and offer feedback on the child’s capabilities and strengths, as well as strategies to help the child perform the job or a specific task.

“Some of these children have really significant disabilities that we really don’t see in the U.S.,” O’Donnell says. “It’s just amazing seeing how capable they are.”

With the launch of the country’s first OT program in 2013 at the University of Ghana, USC students took on another role serving as mentors to incoming Ghanaian students.

Since OT is so tied to culture, Nakasuji and Yamazaki wanted to assist Ghanaian students without imposing an American perspective on OT.

“They don’t have any [Ghanaian] OTs yet, since the first class from the university hasn’t graduated yet, so I don’t know what OT will look like in Ghana,” Nakasuji says.

Adds Yamazaki, “We’re at this interesting place where we really want to support [the university] and spread OT to new places, but we don’t want to intrude on their own culturally relevant professional identity.”

Nakasuji thought an email exchange program between the two sets of students would be the ideal solution.

“The [Ghanaian] students have a resource for getting information about how OT works in certain situations,” Nakasuji says. “It’s a way for the OT students to develop a professional identity when there are no OTs in the country . . . and this is a perfect leadership activity for our students.”

A Worldly Perspective at Home

Year after year, USC students tell Nakasuji how their experience in Ghana has profoundly impacted how they practice OT.

“It completely changed the trajectory of my career,” says O’Donnell, who now works in pediatrics. “I realized I’m meant to be working with kids; these trips have given me a passion.”

Adds Yamazaki, “I’m much more aware of how to support the whole family and each client’s unique family context, whether they live across the world or down the street.”

“My first trip really reminded me why I wanted to become an occupational therapist in the first place: to help people be able to do the things that are most meaningful to them.”

— Sophia Lin Magaña MA ’07, OTD ’08

O’Donnell and Yamazaki most value Nakasuji’s lessons in cultural fluidity over cultural competency, a term often used by medical organizations, including the American Occupational Therapy Association.

“Cultural competency implies something static. It makes us feels we’re accomplished when we never will be,” she says, referring to the ways in which cultures change over time.

Nakasuji teaches students to bask in the cultural differences of Ghana, and to apply that same openness when working with a client at home.

“It’s easy to see differences when you’re working with someone who’s very different,” Nakasuji says. “But I want [OTs] to keep that same mindset when working with someone very similar.”

While a clinician and patient might share experiences — the same hometown, ethnicity and religion — Nakasuji says an OT can never fully understand the client’s experience, culture or context.

“As therapists, we think we’re more culturally competent than we are,” she says. “I believe that we’re all very different. For us to be truly client-centered, we must maintain an openness that has to be culturally fluid.”

About Ghana

Location: Africa’s west coast

Population: 25.7 million

Land mass: 92,098 square miles (about the size of Oregon)

Capital: Accra (approx. 42 miles from the Mephibosheth Training Center)

Official language: English

Top 3 occupations: 56 percent agriculture, 29 service industry, 15 percent manufacturing

Doctor-patient ratio: .09 doctors: 1,000 patients

Life expectancy: 64 for men, 68 for women

Source: CIA World Factbook

⋯