Response to COVID-19: PKUHSC Program Transitions to Online Teaching Even Before USC Chan

February 4, 2020

PKUHSC instructors Dr. Hui (Angela) Wang and Dr. Liguo Qian quickly shift classes online and adapt to accommodate stay-at-home orders in Beijing.

Academics and Courses China Initiative Community and Partners Pandemic

The first time Dr. Hui (Angela) Wang met her students was on January 4th, 2020 — during the last week of the PKUHSC fall semester. Dr. Wang, a China Initiative scholar, had completed her Master’s in Occupational Therapy at USC Chan, and just returned to China to continue her Post-Professional Doctorate of Occupational Therapy (OTD) remotely. As one of the inaugural instructors for the PKUHSC Master’s program, she was preparing course content for the adult physical rehabilitation practice immersion, starting the following winter semester, and arranging Level I fieldwork placements. Then COVID-19 happened, and beginning on February 4, 2020, everyone was instructed to stay home.

As Dr. Wang explains, “No one realized it would be this serious. We got the news right before our Chinese New Year Spring break. We just thought [we would] take a long break, and everything would be normal by the end . . . [that we would] just stay at home for a couple days and we would go back.”

However, nearing the end of the Chinese New Year break, it became clear this was not the case. “We [received] notice that they weren’t allowing people to go back [to in-person classes],” Dr. Wang recalls, “it was out of our control and out of the control of the program.” She continues to describe how the transition to online teaching came with several challenges, from having to figure out the infrastructure for online learning, to constantly adapting the course content, and coming up with ways to keep students engaged.

First, the online instructional platform (similar to Blackboard used at USC) that existed at PKUHSC was previously only used to facilitate continuing education courses for healthcare workers, and not by students and most faculty. Though PKUHSC was able to extend access to this platform for student and faculty use, it was unfamiliar and a learning process to adapt in a matter of days. Second, no virtual meeting room platform (similar to Zoom) was commonly accessible at PKUHSC prior to the pandemic. Instructors had to acquire special permission from PKUHSC to obtain a WebEx account that allowed for online teaching. The platform was later changed to Tencent VooV, as it was easier to use.

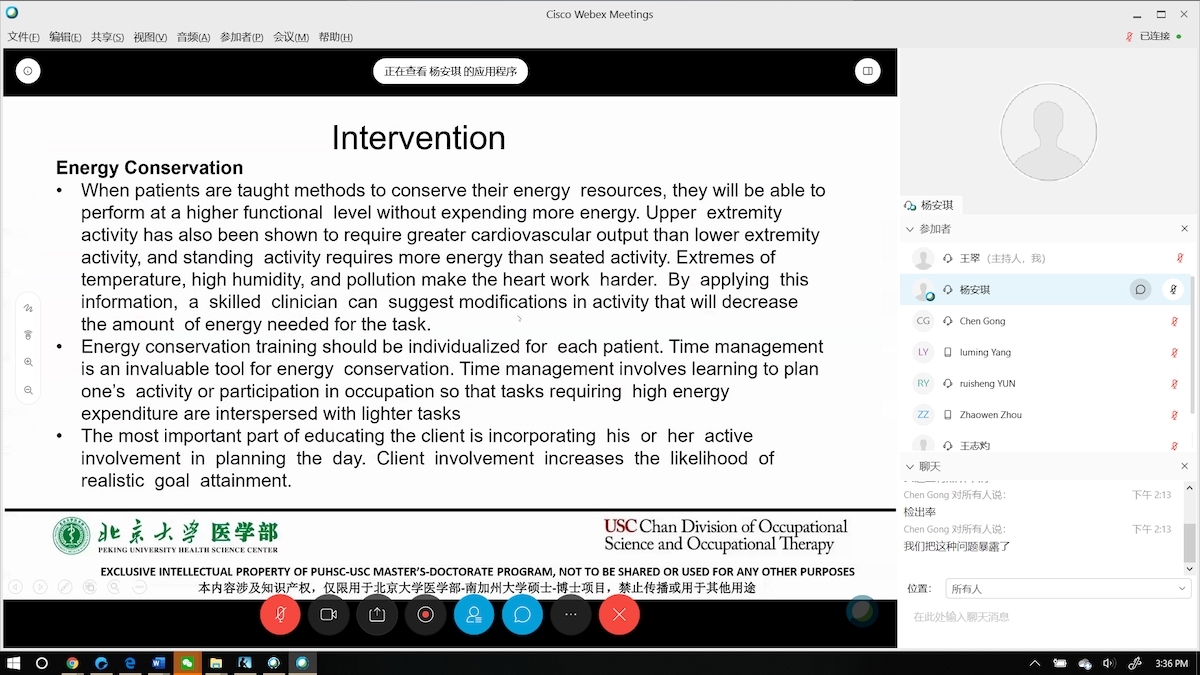

PKUHSC instructors and students adapt to the COVID-19 pandemic and shift classes to WebEx, an online video conferencing platform

Even after the online instructional platform was finally set up, virtual classes continued to prove challenging as technical issues arose. “The meeting rooms couldn’t handle all the students having their cameras on during presentations,” Dr. Wang described. “Most of the time, we had to have them turn their cameras off just so they could hear my voice to take in the content. At that time, we felt disconnected and those were things we had no control over.”

Another limitation imposed by the stay-at-home order was that students would not be able to participate in their in-person Level I fieldwork experiences. The instructors had to continuously shift the program timeline, trying to strike a balance between adapting to the current circumstances, and still preserving the quality and integrity of the course content. “We definitely had to change our teaching methods in order to support the students’ learning experiences,” Dr. Wang recalls. The result was that all the Level I experiences included some component of online learning experience consisting of self-reflections, discussions, video watching, and article reading. Students were then able to make up the rest of their Level I FW experiences in-person in the second year of the program.

Without the in-person Level I fieldwork to pair with the course immersion content, students had difficulty connecting the theory and content being taught in the classroom to practice. In response, Dr. Wang incorporated more case studies into the course curriculum to help students translate the content more directly and encouraged more discussions to reason and process through together. She also recalls having to be very creative by finding and using different kinds of learning aids and resources, including research articles and videos, so that students would have varied learning experiences.

As time went on, Dr. Wang felt she was able to see some of the benefits of the online classes. “The typical teaching environment in China is: the instructors teach and the students learn,” she explains, but through online classes the instructors implemented a lot more opportunities for discussion and reflection. This helped improve the students’ communication and reflection skills and showcased more of their insights. “In the beginning it was very silent, and I would have to find creative ways to engage the students,” she recalls. With just 6 students in the inaugural class, she came up with the idea of rolling a dice and assigning 1 student to each number. That student would then have to answer her questions or contribute to the discussion if their number was rolled. By the end of the semester, students were so used to contributing to the classroom discussion that they no longer needed the dice to encourage them to participate.

⋯